Updates from Adam Isacson (May 21, 2024)

Hi, this is Adam. If you're receiving this message, it means you signed up on my website to receive regular updates. If you'd like to stop getting these, just follow the instructions further down.

I'm back from a few days in Medellín, Colombia, where I spoke at a very good migration conference at the Universidad de Antioquia. Some highlights from that trip are below.

Now I'm starting a two-month sabbatical—two days in, as I write this—which so far has given me the time to take a deep breath and do a bit more writing on my site, including some number-crunching. Some links to that are below.

Last week's travels kept me from doing a weekly border update; I've since been posting daily ones that will become a weekly edition by Friday. This e-mail does, however, have weekly events links (16 of them) and links to some good readings.

Video of Last Wednesday's Panel on Migration in Medellín

Here’s last Wednesday’s panel at Medellín, Colombia’s Universidad de Antioquia, where I presented with Carolina Moreno of Bogotá’s Universidad de los Andes. (It’s in Spanish, which means that viewers have to puzzle through my Spanish. I’m not much more articulate in English, honestly.)

Until I ran out of time, I spoke about current migration trends, what’s happening with U.S. border and migration policy, and the poor choices that countries have for managing in-transit migration.

You can download a PDF file of the slides I used at bit.ly/2024-adam-unal-med.

My deepest thanks to professors Lirio Gutiérrez and Elena Butti of the Universidad Nacional Sede Antioquia for leading the great team of faculty and students who have organized this two-day conference. I’ve learned a lot from the panels.

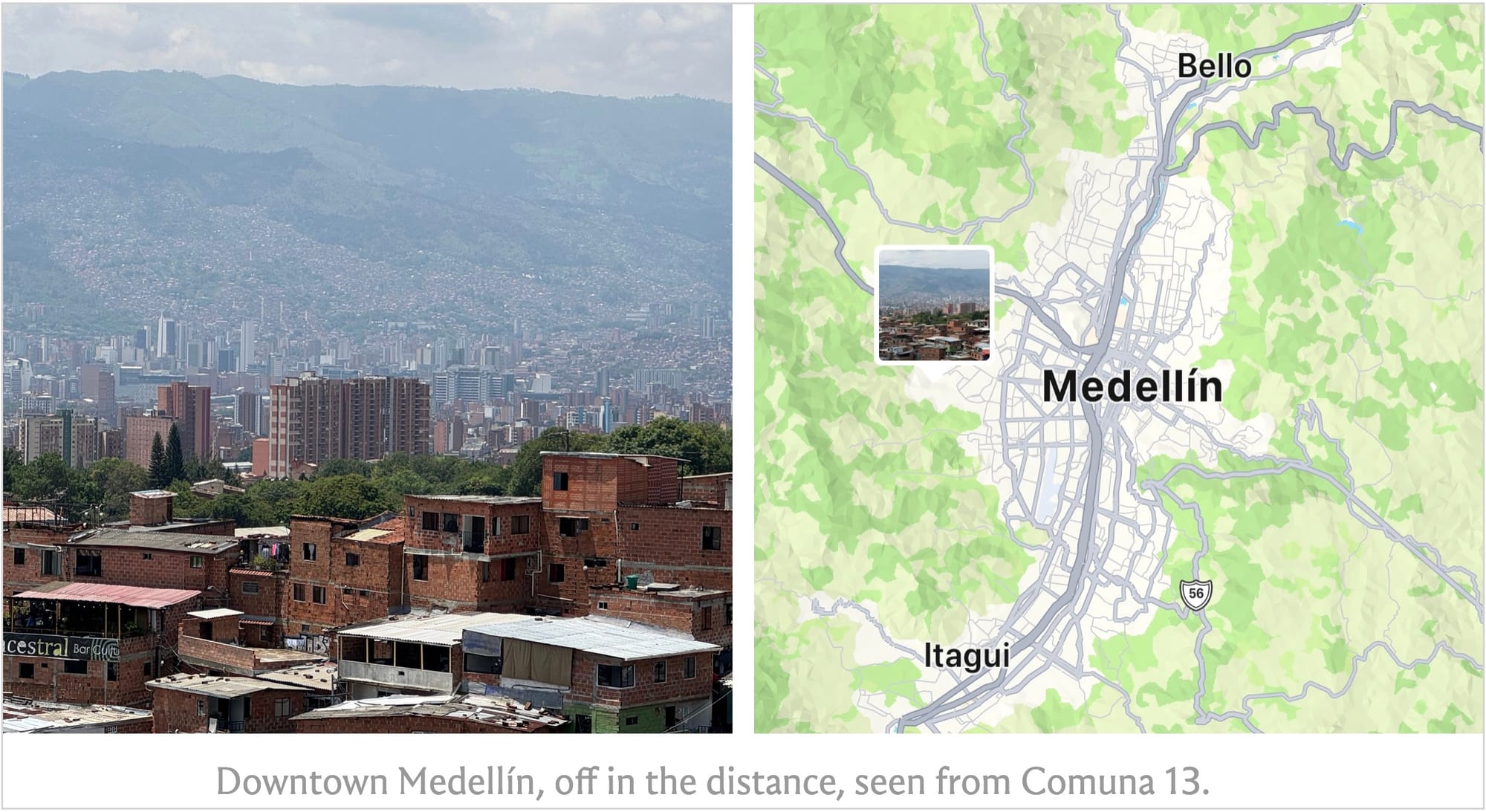

Medellín’s Comuna 13, 22 Years After Operación Orión

I had a few hours off in Medellín last Friday to see an important part of the city that I’d visited in 2006 and 2013. Here are some quick notes.

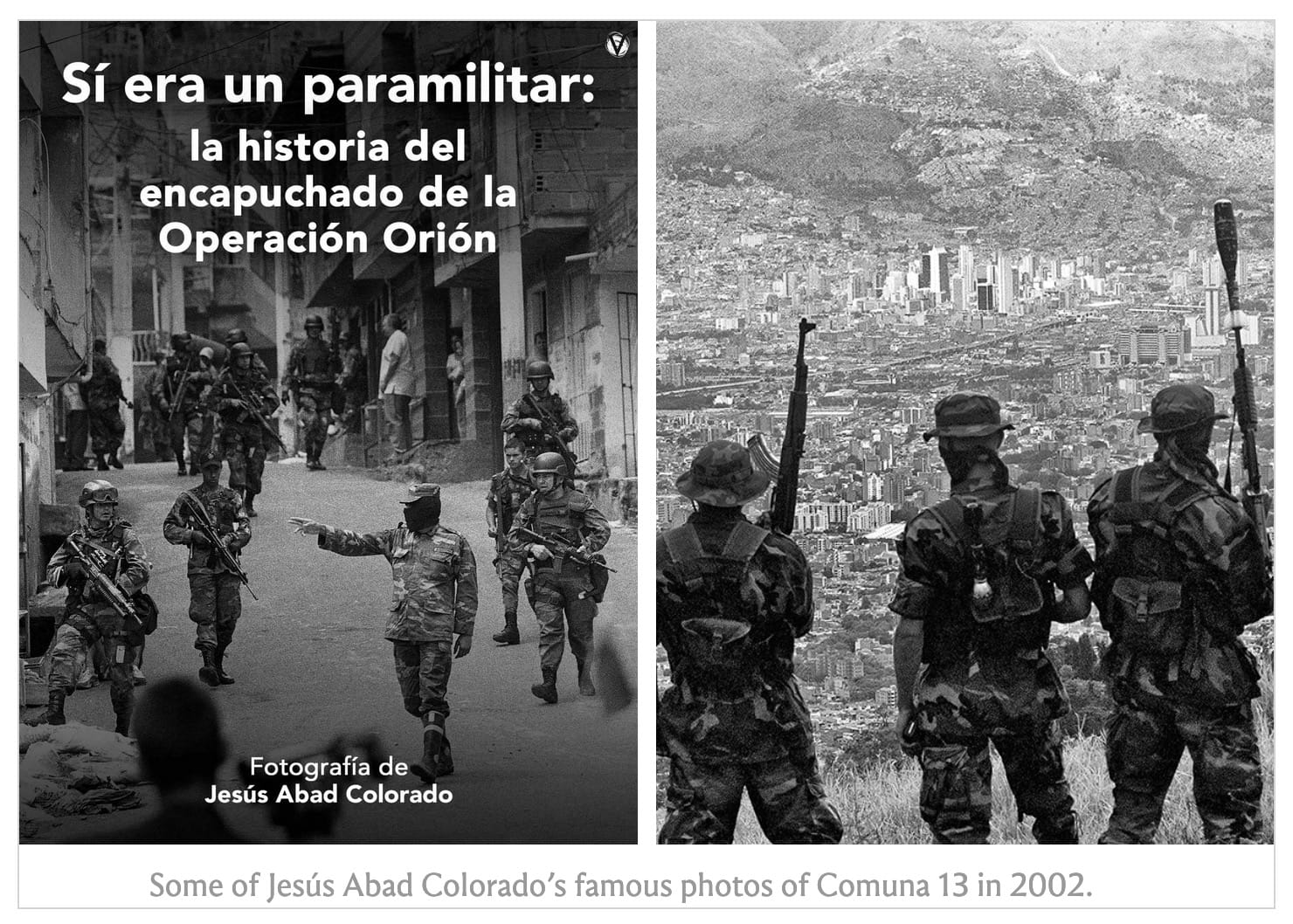

Comuna 13 is a set of neighborhoods on the western edge of the city, first settled—often by forcibly displaced people—in the 1970s and 1980s. It was a “no go zone” for the rest of the city for many years, known for government neglect and gang violence. Guerrilla militias were dominant in the 1990s. Then, in 2002, the new government of Álvaro Uribe launched an intense military offensive in the neighborhood, “Operación Orión.” Soldiers and police fought hand-in-hand with brutal paramilitary groups to root out the guerrillas. Dozens were killed and disappeared; people still find bodies buried nearby.

The paramilitaries took over criminality in the neighborhood, which today continues to have a heavy gang presence. But Medellín’s mayors also started investing very heavily in Comuna 13, integrating these abandoned areas into the city’s civic and economic life, often working with community organizations.

See a report from my 2006 visit to Comuna 13 here (starting on page 11), with some photos of what the neighborhood looked like then. See, in Spanish, the National Center for Historical Memory’s report on Comuna 13 in 2001-2003.

So anyway, it was jarring to see the neighborhood now, after so many years. It is far more peaceful and prosperous, as gang disputes have eased and the government’s investments have borne fruit.

But most bizarrely, Comuna 13 is now a tourist destination. Not really because of its violent history—though hired guides will tell you about what happened there—but because it is accessible, has great views, and offers casual travelers a gritty, edgy, graffiti-artist atmosphere that you don’t find elsewhere in this business-friendly city of expressways and shopping centers.

So where not so long ago there were running battles and forced disappearances, you can take a series of escalators to areas stuffed with the kinds of bars and shops where you can buy a cannabis-infused beer and a Pablo Escobar t-shirt, or get tattooed. (There are more creative sites there too, but they’re being crowded out by a lot of stuff that…well, let’s just say it’s not for me.)

Comuna 13’s poverty is still there, very much in plain view, which makes the party vibe even more jarring. What I saw today is preferable to what I saw in 2006, but Comuna 13 is still, without a doubt, a very hard place to grow up or raise a family.

I’m glad I saw it, and I’m glad that Comuna 13 is now easy to get to from the rest of Medellín, and is now considered an important part of the city.

Texas Gets No Credit for 2024’s Drop in Migration

Of Joe Biden’s 39 full months in office, 2024 so far has seen the months with the third, fourth, eighth, and ninth fewest migrants apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border. April was fourth-fewest.

This was unexpected, since it immediately followed some of the Biden administration’s heaviest months for migration, including the record-setting December 2023. The drop appears to owe to a sustained crackdown carried out by Mexico’s government, with migration agents, national guardsmen, and other security forces blocking migrants’ northward progress.

The governor of Texas, Greg Abbott (R), has been claiming that his state government’s border crackdown reduced migration there and pushed it to states further west. That’s not what the data show.

Since record-setting December, and also since migration dropped in January, Arizona—not Texas—has seen the sharpest percentage drop in migration. Arizona has a Democratic governor, and its state government is not carrying out a severe deterrent policy like Abbott’s $10 billion-plus “Operation Lone Star.” Yet Arizona’s migration reduction is similar. So Texas doesn’t get the credit.

We can zoom in further to look at what has happened to migration in each of Border Patrol’s nine U.S.-Mexico border sectors.

Viewed this way, one of Texas’s five sectors did see the sharpest drop in migration: Del Rio, in mid-Texas, fell 86 percent from December to April; 39 percent from January to April. It is the only Texas sector to have decreased more sharply than the border-wide average.

But Tucson, Arizona—Border Patrol’s busiest sector between July 2023 and March 2024—fell almost as steeply as Del Rio (61% since December and 38% since January).

And after a December-January drop, all other Texas sectors are increasing.

Del Rio’s migration decline was led by super-sharp drops in arrivals from Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua, three nationalities (along with Haiti) whose citizens the Mexican government allows the Biden administration to deport into Mexico under its May 2023 post-Title 42 “asylum ban” rule.

Deportation into Mexico without allowing a chance to seek asylum is almost certainly illegal: a federal judge already struck this part of the rule down (it remains in place pending appeal). It’s possible that this practice—more than Texas’s concertina wire, buoys, and soldiers—may have affected the choices these nationalities’ migrants made in Del Rio since January.

Border-wide between January and April, for every Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, or Venezuelan migrant who crossed the border irregularly (43,040), more than five instead arrived via legal channels: either the “CBP One” app (about 120,000) to make appointments at ports of entry, or the Biden administration’s humanitarian parole program (about 108,000) for these nationalities.

In Tucson, no nationalities declined as steeply as did Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, and Cubans in Del Rio. But the drop has happened across the board, with only modest increases in apprehensions of Colombians and Peruvians.

From what we know of the month of May so far, migration along the border could be declining even further. Twitter reports from the San Diego and Tucson Border Patrol sector chiefs have showed both regions declining over the past two weeks. The El Paso municipal government’s “migrant crisis” dashboard is also showing flat, even slightly reduced, numbers of encounters there.

WOLA Hits 50

The Washington Office on Latin America celebrated 50 years since its founding on the evening of May 9. As someone who spent the past 14 of those years with WOLA, I was delighted to be on hand at a party with 400 people, all living former directors, and 3 inspiring human rights awardees.

I was home before midnight, then up four hours later to fly to Massachusetts to pick up my daughter at college. A truly great night.

My Way-Too-Ambitious Sabbatical Plans

WOLA gives us a sabbatical every five years: a time to reflect and work on other projects. My last one was in the fall of 2015. Between the pandemic and my procrastination on the “sabbatical proposal,” it’s taken me eight and a half years to start a new one.

I’m lucky to have it. This is a much different period of my life than last time.

- Last time, I’d been doing this work for 20 years and was solidly mid-career; now, I’m entering my mid-50s and thinking about what may be my final 20 (25? 30?) years of doing this work.

- Last time, I was raising a 6th grader; now, she has just finished sophomore year of college.

- Last time, I did not travel. This time, I’m just back from Medellín and headed to Bogotá in June and El Paso for three weeks in June and July. The first two are conferences. The border visit is just me hanging out.

The rest of this is in a long-winded post about what I'd like to work on and think about over the next two months, plus some expectations-setting about how easy/hard it will be to contact me.

I plan to make at least one new website and finish at least one new report, while learning a lot of new things. If interested, read the whole thing here.

At a Migration Conference in Medellín

Here are a few things I learned from fellow panelists at last Thursday’s sessions of a migration conference at the Universidad de Antioquia in Medellín.

- The largest number of people traveling through the Darién Gap get their information about the migration route through word of mouth, followed by WhatsApp, followed by other social media, followed by more reliable sources like humanitarian groups.

- Of all major Colombian cities, Medellín is where business owners report being least willing to hire migrants.

- In Medellín’s north-central Moravia neighborhood, organized crime demands larger extortion payments from Venezuelan small business owners than from Colombians. Most Venezuelans in the neighborhood do not intend to stay in Colombia: they either want to return to Venezuela if things improve, or they plan to move on. So they tend to choose not to mix into community life.

- Among Venezuelan migrants in Colombia, there is a strong correlation between being a woman and the likelihood of being a victim of violence, including sexual violence.

- Many Venezuelan LGBTQ+ migrants are fleeing attacks and discrimination, especially trans people who have it very bad there. But they more often cite “sexual liberation” or the availability of medical treatments, like HIV retrovirals, as their reasons for coming to Colombia.

- Armed and criminal groups causing a lot of displacement and cross-border migration along Colombia’s remote southeast border with Venezuela and Brazil include FARC dissidents’ 10th front, the ELN, Brazil’s Garimpeiros, Venezuelan “sindicatos,” and Venezuela’s armed forces. All are profiting from illicit precious-metals mining and other environmentally disastrous practices, principally on the Venezuelan side of the border and usually in Indigenous territories. States are either absent, or part of the problem.

I Added a Major Website Feature in Less Than 20 Minutes

I keep a little webpage that generates tables of data about migration at the U.S.-Mexico border, using CBP’s regularly updated dataset.

For weeks, I’ve wanted to have the ability to sort the tables by clicking on their column headers. It seemed like a big job, though, especially figuring out how to keep the columns’ totals at the bottom, not included in the sort.

On Sunday evening, though, I thought to ask ChatGPT—and it gave me exactly what I wanted, with only a couple of dozen lines of code. Here’s what the tables can do now:

The whole process took less than 20 minutes: two queries and me copy-pasting the code into the page. It works flawlessly, which is very cool, and perhaps a bit creepy.

(I've since tried out GitHub Copilot, which does this right inside your code editor.)

Latin America-Related Events in Washington and Online This Week

(Events that I know of, anyway. All times are U.S. Eastern.)

Monday, May 20, 2024

- 3:00-4:30 at wilsoncenter.org: Election Series | Discussing Mexico’s Third Presidential Debate (RSVP required).

Tuesday, May 21, 2024

- 10:00-11:00 at wilsoncenter.org: The Dengue Epidemic: A New Test of Latin America’s Health Sector Preparedness (RSVP required).

- 10:00-12:00 at the Inter-American Dialogue and online: Medios y democracia en las Américas VI: El periodismo independiente ante el declive democrático en la región (RSVP required).

- 10:30 in Room 419 Dirksen Senate Office Building: Hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on American Diplomacy and Global Leadership: Review of the FY25 State Department Budget Request.

- 12:00-1:00 at quincyinst.org: A U.S.-Kenyan Rescue in Haiti and its Implications for American Foreign Policy (RSVP required).

- 2:30 in Room 138 Dirksen Senate Office Building: Hearing of the Senate Appropriations State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Subcommittee on A Review of the President’s Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Request for the U.S. Department of State.

- 3:00-4:00 at the Inter_American Dialogue and thedialogue.org: Chile’s Foreign Policy Priorities (RSVP required).

Wednesday, May 22, 2024

- 10:00 in Room 2359 Rayburn House Office Building: Budget Hearing of the House Appropriations State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Subcommittee on Fiscal Year 2025 Request for the Department of State.

- 2:00 in Room 2172 Rayburn House Office Building: Hearing of the House Foreign Affairs Committee on The State of American Diplomacy in 2024: Global Instability, Budget Challenges, and Great Power Competition.

- 2:00-3:00 at USIP: Haiti and Development: Learning from Successes (RSVP required).

- 3:00-4:00 at csis.org: Combatting Transnational Drug Flows: A Conversation with Admiral LeGree (RSVP required).

Thursday, May 23, 2024

- 10:00 in Room 2200 Rayburn House Office Building: Hearing of the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Oversight and Accountability on Money is Policy: Assessing Shortcomings in the State Department’s Foreign Assistance Grants Process.

- 2:00-3:00 at the Wilson Center and wilsoncenter.org: Bridging Histories, Forging Futures: Celebrating 200 Years of Brazil-US Relations (RSVP required).

Friday, May 24, 2024

- 8:15-9:45 at thedialogue.org: The Security Challenge for Democracies in Latin America (RSVP required).

- 10:00-11:00 at brookings.edu: Haiti on the brink: The prospects and challenges of the Kenyan-led MSS initiative (RSVP required).

- 10:00-11:00 at the Inter-American Dialogue and thedialogue.org: A Fireside Chat with Lourdes Melgar (RSVP required).

Links From the Past Week

Carlos Bravo Regidor, Sarah Birke, Mexico's Politics of Bitterness (The New York Review of Books, Monday, May 20, 2024).

On the eve of Mexico’s presidential elections, Andrés Manuel López Obrador maintains a high approval rating. But his constitutional chicanery and disregard for the law have undermined democracy, and his divisive rhetoric has polarized the country

Julian Rios Monroy, Sur de Bolivar: La Guerra por el Oro Que Enfrenta a Clan del Golfo, Eln y Emc (El Espectador (Colombia), Sunday, May 19, 2024).

Los combates son solo la punta de un iceberg que esconde reclutamientos, extorsiones, desplazamiento y explotación sexual. Las comunidades denuncian connivencia de Ejército con grupos ilegales

Denise Dresser, Mexico's Vote for Autocracy (Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico, Foreign Affairs, Friday, May 17, 2024)

López Obrador has undermined democracy and brought back dominant-party rule

Santiago Rodriguez Alvarez, Adentro del Laboratorio de Paz Territorial de Petro Con la Disidencia del Eln (La Silla Vacia (Colombia), Monday, May 13, 2024).

La Silla estuvo en las montañas de Nariño donde se dan los primeros pasos en el proceso de paz con el Frente Comuneros del Sur

Steven Dudley, How Mexico Loses the Precursor Chemical Money Trail (InsightCrime, Wednesday, May 8, 2024).

Mexican authorities have never identified any money laundering cases related to synthetic drugs or precursors in Mexico, according to our public records requests and interviews with officials

And Finally